I love this Article from SURFER Magazine.

The future of Jamaican Surfing is looking Brighter than ever.

Take a look mon.

This is SURF ROCK REGGAE 😉

By Ashtyn Douglas

for SURFER Magazine.

Ivah Wilmot’s sun-bleached dreadlocks dangle over a pile of surfboards as the 19-year-old bends down to pick up a groveler with a green, gold, and red stomp pad. It’s a wide-nosed Sharp Eye—probably no bigger than a 5’6″, by the look of it under his taut, chiseled arm. The deck is covered with craters and the rails have a few patched dings, but by Jamaican standards, the board is mint.

“An American surfer named Tyrone gave this to me when he was visiting,” Ivah tells me, holding the board out in front of him for us both to examine. He’s shirtless with an oversized shark-tooth pendant hanging from his neck. “He noticed I didn’t have a fresh board, and he was like, ‘Oh, mon, you rip. Take this.’”

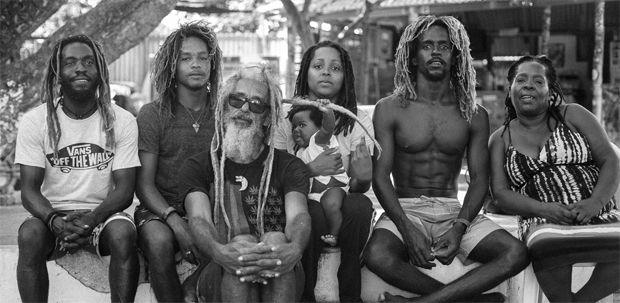

Looking for relief from the sweltering Jamaican sun, I had asked Ivah to show me his quiver in Jamnesia Surf Camp’s boardroom. Jamnesia was started along the south coast of the island by Ivah’s father, Jamaican surfing legend and prominent reggae musician Billy “Mystic” Wilmot. Ivah and his four older siblings learned to surf the wave-speckled shores outside Kingston and quickly became the island’s top talent, winning both domestic and international competitions in their respective age groups. Ivah is part of Jamaica’s new generation of rippers, with a style that pays homage to the knock-kneed, light-footed comportment of Craig Anderson or Rob Machado.

Inside Jamnesia’s boardroom, the sun seeps in through shuttered windows, silhouetting a library of aging boards scattered throughout the room. A beige Channel Islands shortboard with weather-beaten full traction leans against the wall, pummeled with pressure dings and patched back together in two different places. Yellowed single-fins and heavily rockered ’90s chips hang from the ceiling alongside a few stubby twin-fins with wide tails thick with resin from repair jobs.

“Yeah, mon. I’ve surfed all these boards in here. Those up there were my dad’s boards that I grew up riding,” Ivah says, pointing to the overstuffed rafters. “Back then you got a board and that was your board for a year and a half. You surfed that board even if it didn’t feel right. You just figured it out.”

Like Ivah, most Jamaican surfers grow up riding whatever craft they can get their hands on. There are no surf shops or shapers on the island, which means any surfboard that finds its way to this corner of the Caribbean comes from abroad. Most local surfers, however, come from working-class families and live off roughly $50 a week as fishermen or laborers just to put food on the table. For them, ordering a board from another country is pie in the sky.

High shipping fees and import taxes keep boards even farther out of reach. Once the customs tariff is tacked on, a $600 foreign-made surfboard quickly becomes $800 or $900 or more—a premium price tag, even for Americans making a comfortable living. One Jamaican surfer later explained, “It’s almost as if we’re buying the surfboard twice.”

Foam blanks, fiberglass, and resin are also subject to a steep import tax, which has discouraged surfers from shaping and manufacturing their own boards. In the end, most locals rely on traveling surfers leaving their boards behind.

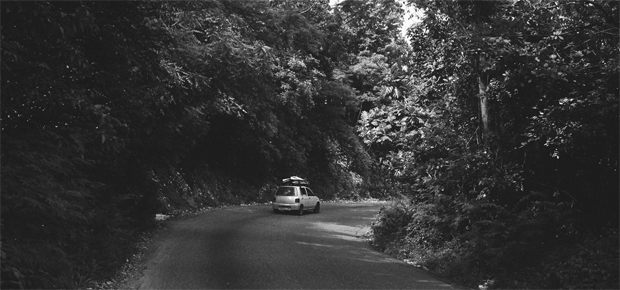

Despite being cut off from the surf industry, Jamaica’s surf culture has experienced decades-long slow growth. The island’s perimeter plays host to a handful of punchy, rippable reefbreaks and a bevy of unsurfed waves cloaked by inaccessible roads. It’s an idyllic, relatively empty playground for surfers like Ivah to hone their technique. And with the small collection of secondhand boards sitting at Jamnesia, the Wilmot family has been able to keep the stoke of surfing alive for other kids, teaching them how to surf and supplying the few boards they have to those in need.

“We used to have a lot more boards around here,” says Ivah. “But we end up giving away older boards to people. I’ll surf a board for a while and then send it over to Boston Bay, a town to the northeast. There are a few guys over there who I keep an eye on and make sure they always have boards and wax. Little things make a huge difference here.”

Ivah carefully places his Sharp Eye back down on the pile of boards and nods toward the door. “But I’m guessing I won’t have to do that anymore after today.”

Outside the boardroom, the concrete yard looks like a surf swap meet gone off the rails. The ground is completely covered with boards—205, to be exact—of varying sizes and designs: Al Merricks, Xanadus, Arakawas, DHDs; single-fins, twin-fins, thrusters; stickered, not stickered; hi-fi, low-fi, and everything in between. It’s almost dizzying, even for a Californian, seeing this many unique boards in one place.

Just behind him is a 30-year-old chef named J.J. sifting through a mound of boards, searching for something that will float his 6’4″ frame. “I’ve been surfing since I was 7,” he says, picking up a board with too little volume and swiftly laying it back down. “But I’ve never had the opportunity to ride a good board.” He stoops down and grabs a hefty 6’7″ pintail shaped by Robin Mair. A grin spreads across his face.

“Last time we were in Jamaica, about two years ago, we were blown away by the talent and passion the locals had,” says Dane Gudauskas, who, along with his brothers Pat and Tanner as well as Dylan Graves, is busy passing out boardshorts and helping kids choose suitable sticks. “But things weren’t adding up with the boards. It just looked like there were no quality boards for how good these kids were surfing. So we started asking questions. They told us about the taxes and the lack of existence of any sort of surf industry here.”

Upon returning to the States, the Gudauskas brothers started devising a plan to help out their friends at Jamnesia through their charitable foundation, Positive Vibe Warriors. For months they raised awareness via social media about the scarcity of surfboards in Jamaica and urged Southern California surfers to donate used (but watertight) boards to any Jack’s Surfboards locations. Once all 205 boards were collected, they were sent to Jamnesia in a 40-foot shipping container, along with tubs of resin, boxes of wax, fins, and leashes.

According to Billy Wilmot, the arrival of these boards marks a major moment in Jamaican surf history. “Many people have come through here making promises about helping,” he says. “But up until this point, the help we’ve gotten was tiny and scattered. This isn’t just a couple of donated boards. This is a lot of boards donated to the nation of Jamaica.”

Billy’s other son, 29-year-old Icah, was Jamaica’s first pro surfer and currently teaches surf lessons at Jamnesia. Icah believes this will give local kids admission to a new lifestyle—one that will hopefully keep them out of trouble in the impoverished communities that line the south coast of the island. “Surfing helps them keep their focus in the water and keep that whole negative side of the world at bay,” Icah says. “Instead of looking toward land and seeing corruption and violence in the city, they can focus on the sea, an open world with endless possibilities.”

A group of kids grab their new boards and make a dash to the gentle, user-friendly break out front. Graves and the Gudauskas brothers are right behind them with bars of wax and fins that need to be screwed in. The waves are 1 foot, generously speaking, but the stoke is huge.

Haile stands at the water’s edge with his leash already strapped on, watching his older brother, Selah, snag a little left. He tells me he’s excited to surf, and I ask how long he’s wanted to learn.

“Well…” He pauses for a moment. “I decided I wanted to surf starting today, when someone told me I could pick out my own surfboard.” Within minutes, Haile’s out in the lineup with the rest of the kids and the instructors. One by one, they all catch small, dribbling waves using what seems like an innate ability and comfort in the water. Two kids who had never surfed before catch the same wave, squatting low to maintain balance until their paths collide. They both come up giggling.

Judging by the smiles and laughter emanating from the lineup, the initial positive impact of the board drive on the local community is clear. But what about the future of Jamaican surfing in the long term? Is one kind act enough to sustain a developing surf culture? What happens when these kids show their friends how to surf, their friends teach others, and so on? It seems like it’s only a matter of time until Jamaican surfers once again outnumber the available resources.

According to the Wilmot family, getting to that point will be a good thing. “The solution is getting more kids interested in surfing, because the more kids you have wanting to surf, the more need there is for boards to be accessible,” says Icah. “People will start going to sporting-goods stores, asking for boards. If the demand grows, the supply will follow—which is what we’re trying to do with Jamnesia. If surfing is the next big thing, then businessmen will want to get involved.”

Later that day, Graves, the Gudauskas brothers, and I follow Ivah and his friends, Shama Beckford and Garren Pryce, to Makka, a left-hander breaking over a shallow reef on the east side of the island. The lineup is empty, save for a windswell churning out a procession of non-stop waves.

About halfway through our session, Graves hands Shama his own board to try on for size: a 5’5″ Haydenshapes. Shama, one of Jamaica’s most radical surfers, with an affinity for ankle-busting aerial maneuvers, heads straight to the peak. Thirty seconds later he picks off one of the day’s bigger sets. He banks hard into a deep bottom turn, heads for the lip, and hits it just as the lip begins to feather, sending a torrent of crystal-clear saltwater down on the rest of us before he zooms down the line and hucks a huge air reverse on the inside section. It’s a ride that would earn an excellent score at any ’QS event.

As Shama returns to the peak, I ask how the board felt under his feet. “It’s fast, fits into the pocket, and the transitions are amazing,” he says excitedly, like a kid who got exactly what he wanted for Christmas. “Good equipment brings out the best in your performance, you know?”

Watching Shama beaming after his ride, I’m reminded of what Billy told me earlier: the donated surfboards don’t just benefit the many local kids eager to learn how to surf; they provide an opportunity for more-established talents like Shama and Ivah to continue improving and realize their potential.

“You can see how well these kids surf and how far they’ve gotten with what they have,” Billy said. “Imagine what they can do with access to more resources. Now they’ll be able to try to stick airs without being afraid that their board will break. This is going to push the level of surfing in Jamaica, just by having these boards.”

Ashtyn Douglas is the Associate Editor for SURFER Magazine.

November 2016 Issue.